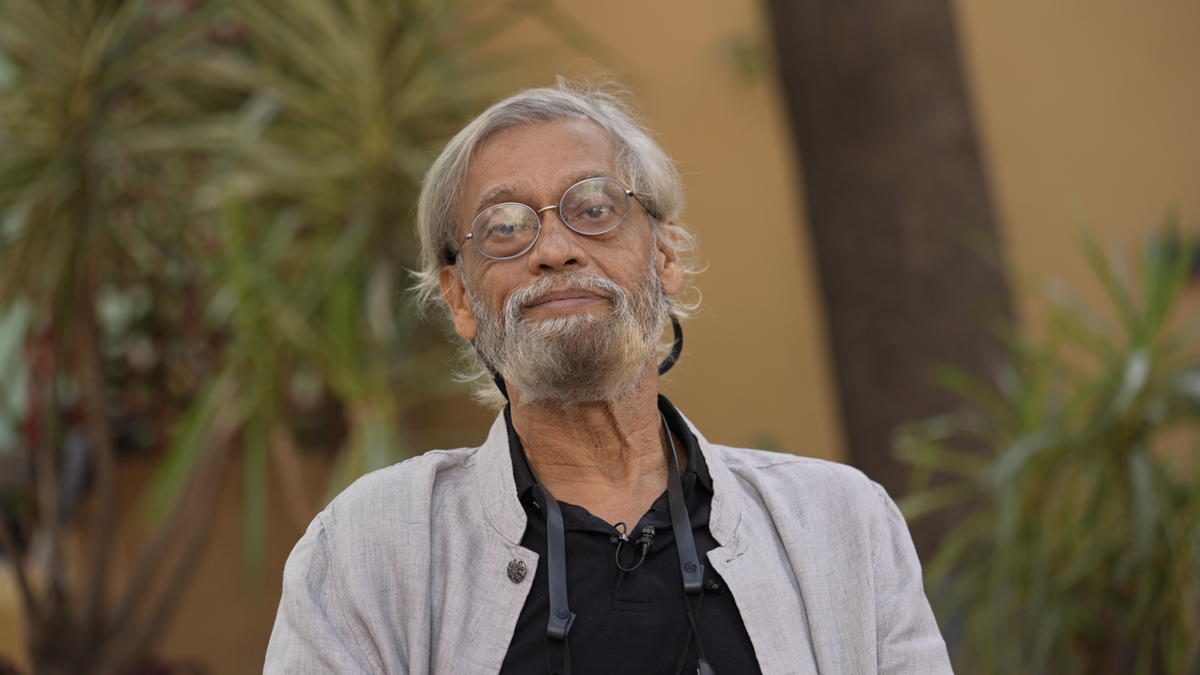

“No critic asks me why I name a film set around the Emergency after a Ghalib couplet,” wonders Sudhir Mishra amid an intense conversation. Two decades after Hazaaron Khwaishein Aisi, a tale of unfulfilled desires set against the Emergency and the Naxalite Movement stirred our souls, director Sudhir Mishra is mounting another drama set against the politically volatile period.

Spread over eight episodes, the title Summer of ‘77 sounds like HKA in long form. The deep fissures on Mishra’s face give way to a gentle smile. “It is about six-seven characters from different social backgrounds involved in the JP Movement who question the idea of India handed over to them by their fathers. It is about rebellion, relationships, and politics in between. It is set in a space where old structures were breaking and new women were emerging to claim rights over their bodies. They no longer wanted to be owned by a relationship or a man. Some were much more experimental in their worldview than today’s women.”

It is not HKA, he avers, but as the filmmaker is the same, he says, the audience will see a part of him, his viewpoint on life. “While HKA veers towards the Naxalite movement, Summer of ‘77 is about the movement started by Jai Prakash Narayan. In HKA, the three characters hail from a niche class, which we can call Indian desis for want of a better word, who struggle to find their own India. Here, the characters come from the mainstream middle class, and they are reacting to their India being taken away from them. That is how it speaks to today’s audience.”

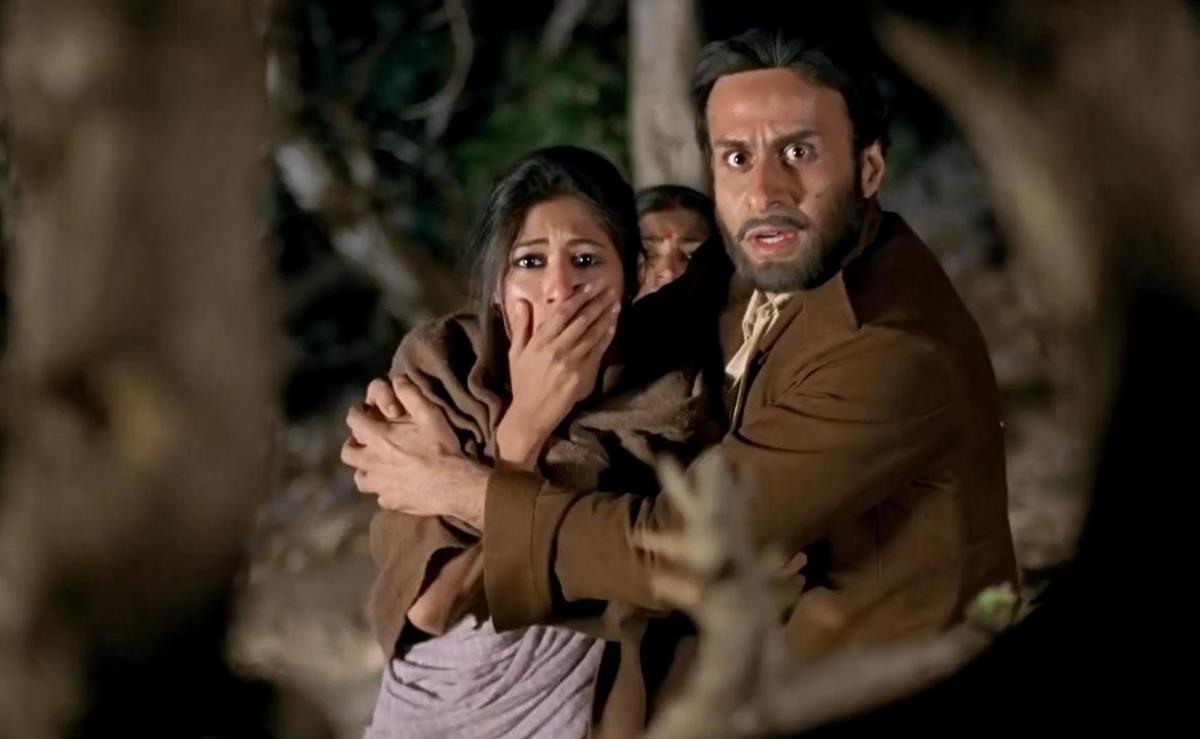

A still from ‘Hazaaron Khwaishein Aisi’

| Photo Credit:

The Hindu Archives

Mishra says he was too young in the 1970s, but his elder brother and uncles were very much interested. Few know that Mishra’s maternal grandfather, D.P. Mishra, was a freedom fighter and a staunch congressman who served as the Chief Minister of Madhya Pradesh in the 1960s. “He walked out of Congress in 1974 because he could not take what was happening in the party. Part of the series is based on his recollection of the period, which he wrote about in the third volume of his autobiography. I have also used the reflections of youth leaders of the period, like Ramesh Dixit, who started as a leftist and then moved to the socialist fold. Then there are observations of academics like Pushpesh Pant that helped me structure the base of the narrative before imagination took over.”

These days, the Emergency period has become a tool for filmmakers to comment on today’s politics. “It is important because the repercussions of that period are being felt now. Most of today’s events are determined by the politics of that period,” argues Mishra, who was part of the jury at the Mahindra Excellence in Theatre Awards this year, where political plays were well received.

Not interested in mere recreation of the past, the filmmaker says, in his universe, “Emergency becomes a metaphor for the thought that every time a political establishment imposes itself, there is a reaction to it.”

He underlines that HKA stays fresh because it is about “young people anytime, anywhere, reacting to the world that confronts them.” They want to realise their potential, but they don’t follow the path offered to them.

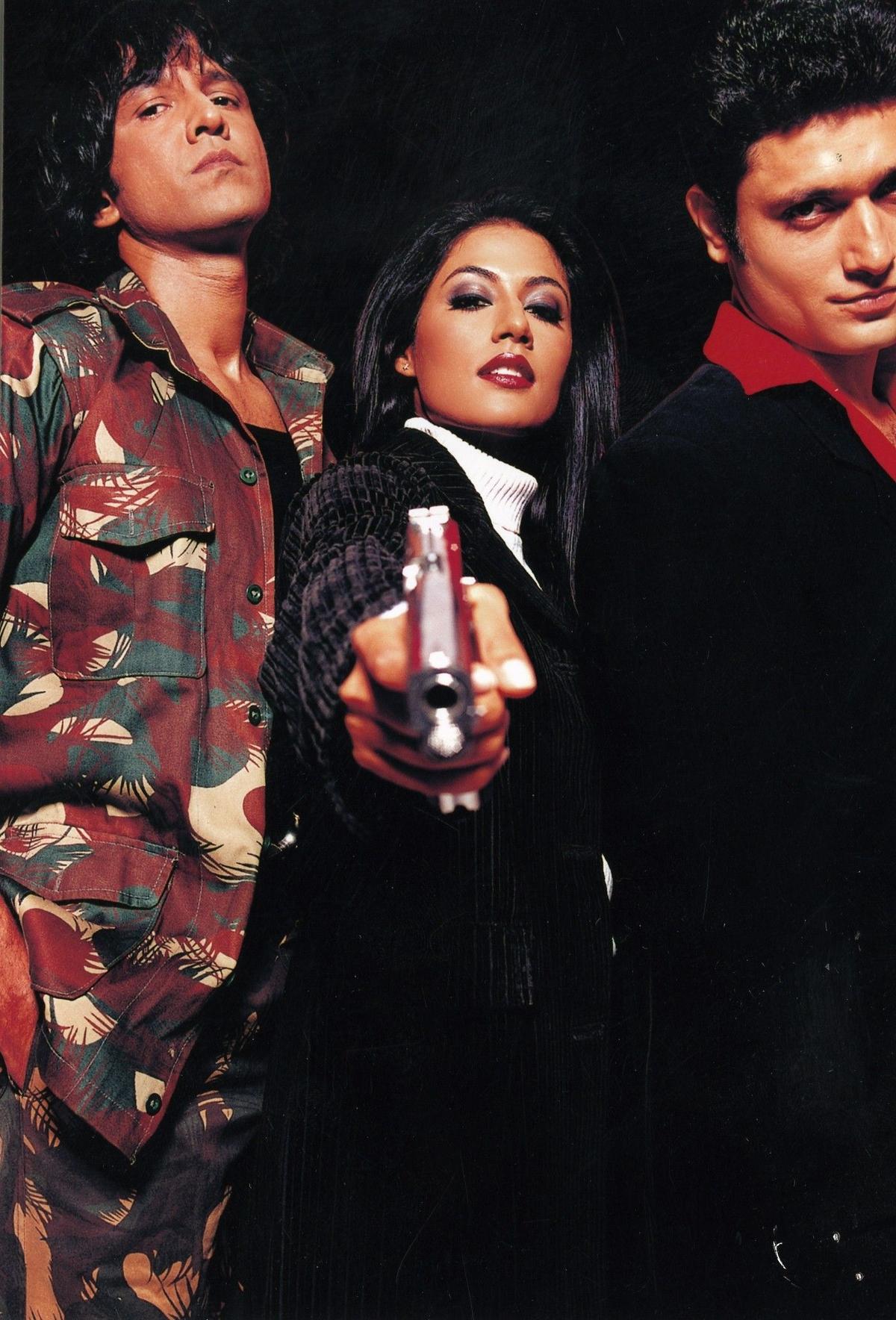

Kay Kay Menon, Chitrangda Singh and Shiney Ahuja in a still from ‘Hazaaron Khwaishein Aisi’

| Photo Credit:

The Hindu Archives

The title, he says, represents Mirza Ghalib’s influence on him. “It is a kind of Sufi view of life. I am not always on the side of my characters. The idealists get scared after watching themselves in the darkness of the theatre. Extreme radicals get miffed.”

Right from Aditya (Nirmal Pandey) in Is Raat Ki Subhah Nahin to Vikram Malhotra (Kay Kay Menon) in HKA, Ayyan Mani (Nawazuddin Siddiqui) in Serious Men, and Rahab (Nawaz) in Afwaah, Mishra doesn’t put his male protagonists, hailing from varied social groups, on a pedestal. More than the heroes, it is Mishra’s muses like Geeta in HKA or Chameli that seem more in control of the situation. “I find women more decisive. They understand loss better. They are willing to admit mistakes more than men.. They are open to accepting what life offers and embracing it. They make for emotionally richer characters,” Mishra muses. It is not that he doesn’t understand his male protagonists. “My men are not weak, but they are frail. They are softer. They make mistakes.” A section of the audience and film stars, he feels, have a problem with that kind of expression. “I don’t think there is any such thing as a permanent hero. Everybody is a hero in some time frame.”

For instance, he says, Rahab lives in a liberal bubble of literary fests. “That world doesn’t open the door for him when he needs it the most. This narrative of finding permanent heroes has destroyed the world. The thought that a hero will come to change the world is flawed. Narratives programmed for a happily ever after scenario, and there is light at the end of the tunnel, don’t often prepare you for life. They become like advertisements for fairness creams.”

On Anurag Kashyap shifting base to South India

Reflecting on his disciple and friend Anurag Kashyap shifting base to South India, Mishra says it seems the Mumbai film industry’s atmosphere was proving stifling for him. “He is reinventing himself. It is not that he has given up hope. His next film, Nishanchi, is set in Uttar Pradesh. I found the statement a bit extreme. I love him, he loves me, but he doesn’t listen to me. He is close to South Indian filmmakers and doesn’t believe in the North-South divide. He is among the first to discuss the need for a pan Indian cinema.”

Mishra feels like the filmmakers, film critics also need to understand life. “Most people who write about films set in the North don’t seem to understand the peculiarities of the region. For instance, in Afwaah, one prominent critic questioned how the villagers didn’t identify Vicky, not realising that he is one small-time MLA in one area of Rajasthan out of 200 in the State.”

Recalling his experience with Chameli, Mishra says not many saw the plot as an impossible situation that talks about the right of a sex worker to say no and overlooked how the film navigates the relationship between her and the pimp. “The film’s success was largely reduced to two songs, Saat Samundar and Bhagey Re Man. They are very nice songs, but there was much more.”

Mishra has delved into mainstream space with films like Calcutta Mail, but it has not been a satisfying experience. “The only way to make a good film is to make one that you would like to watch yourself. The directors who make mainstream films are in sync with the audience of those films. They should not pretend in the evening that they are superior to the audience. They are the audience!”

On his way forward, Mishra says he has decided to go back to being the boy who made Dharavi in 1991. “I want to make films without caring; not going into elaborate systems of Bombay that make cinema expensive, but the investment doesn’t reflect on screen. If you watch Malayalam cinema, they pick up rich subjects, but they are not necessarily big-budget.”

Published – May 09, 2025 03:03 pm IST