In the coming days, white smoke shall billow from the Sistine Chapel’s chimney once more, signaling the election of a new pontificate to the Christian world. The death of Pope Francis at age 88 on Easter Monday, has drawn renewed attention to the intricate and archaic ritual of the papal conclave. The secretive ceremony has been so theatrically loaded that it’s often been catnip for filmmakers over the past century.

For all his modesty and rejection of papal grandeur, the late Holy Father proved to be one of the most cinematically-inclined popes in modern memory. Not only was he portrayed on screen, but he also seemed to inspire a variety of ecclesiastical cinema. During his twelve-year papacy, cardinals, pontiffs, and bishops, both fictional and otherwise, seemed to populate the screen with greater frequency than in any era since the heyday of biblical epics. In a curious twist of fate, the man who eschewed the trappings of office became cinema’s favourite pope.

Newspapers with the front page of the late Pope Francis are seen in London, on Tuesday

| Photo Credit:

AP

The irony, of course, is that the papacy has always lent itself to spectacle, whether the popes liked it or not. And the sealed, whispered process by which 235 cardinals choose a new pontiff is ripe with drama — be it a political thriller in vestments or a crucible of ideology, ego, and God.

Last year’s Oscar-winning Conclave, based on Robert Harris’s novel and directed by Edward Berger, is the latest to capitalise on the eponymous election process. In it, Ralph Fiennes plays a cardinal caught in the crossfire of scandal and revelation. The film’s climactic turn, centering on the sudden rise of a reformist Mexican cardinal with a deeply personal secret, doubles as an homage to the late Pope Francis himself.

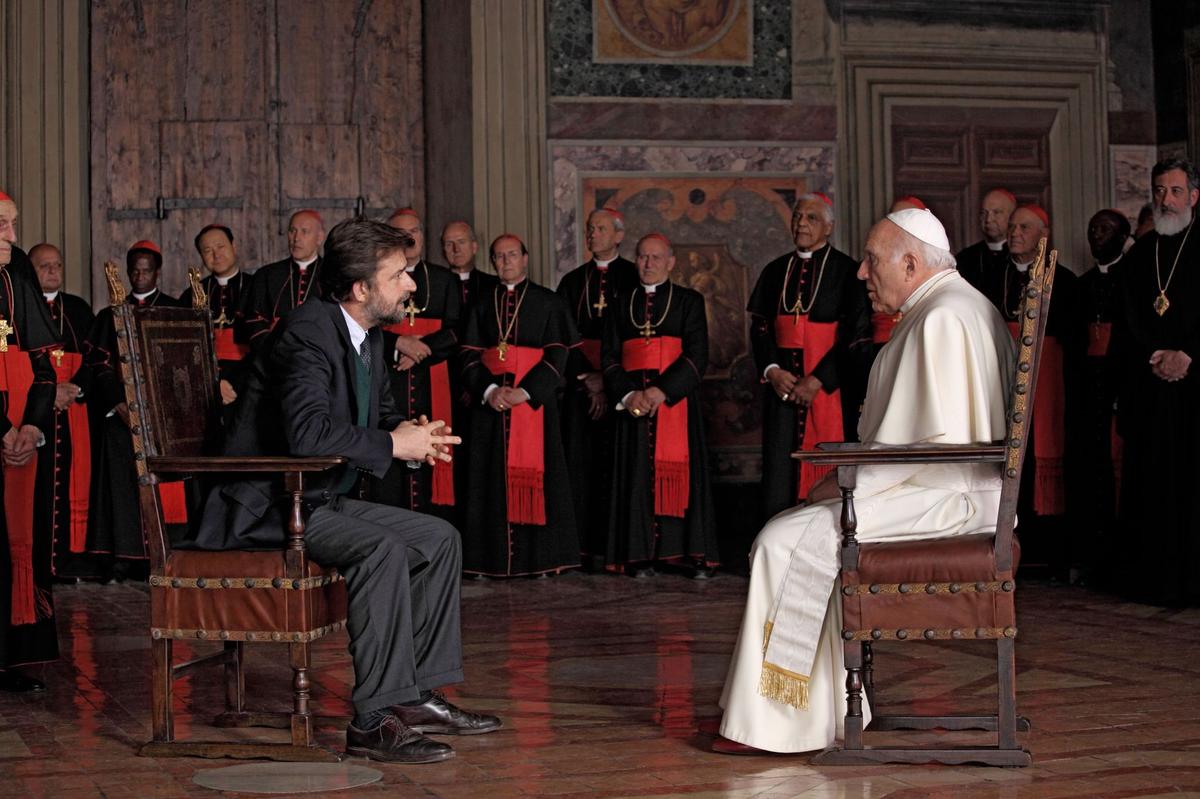

A still from ‘Conclave’

Conclave takes one of the world’s most cloistered rituals and turns it into something bracingly cinematic. It’s a kind of a locked-room thriller that cleverly demystifies the pomp without deflating its gravity. Ballots are burned, secrets are bartered, and the Apostolic Palace steadily holds trial for unchecked ambition. In dramatising the pageantry and paranoia of papal succession, Conclave breaks down and reframes the process as political theatre.

But before Conclave dramatised these cloak-and-dagger rituals, there was Nanni Moretti’s We Have a Pope (Habemus Papam), a 2011 comedy-drama that imagined the burden of papal selection as an existential crisis. The newly elected pontiff, played by Michel Piccoli, flees his obligations, overwhelmed by the absurdity of being chosen to shepherd a billion souls. The film traps the cardinals inside the Vatican, technically forbidden from leaving until the new pope is revealed. Meanwhile, the chosen one wanders Rome and undergoes therapy — administered, naturally, by an atheist.

A still from ‘We Have A Pope’

Moretti’s satire was one of the few to ask, “What if the pope just didn’t want to do it?”; taking the enormity of the position and humanising the Holy Father through unadulterated panic. It also prefigured the deep, sometimes agonised reflection on leadership and discomfort with authority that Francis would come to embody. That a pope might be reluctant (incapable even) was no longer heresy, but human.

Fernando Meirelles’s 2019 drama The Two Popes took that humanisation a step further. In Anthony McCarten’s script, based loosely on real conversations between Pope Benedict XVI and Jorge Mario Bergoglio (later Francis), two men stroll through Vatican gardens, sip Fanta, eat pizza, watch football, and debate God, guilt, and the fate of the Church. Jonathan Pryce plays Bergoglio with a wistful clarity, while Anthony Hopkins’s Benedict is rigid and world-weary. It’s theological chess with a surprisingly warm, even comedic touch, but the film’s main miracle was that it found common ground between two worldviews by treating each as a person rather than a position.

A still from ‘The Two Popes’

But not all cinematic popes are burdened by slow-burning diplomacy. Ron Howard’s 2009 adaptation of Dan Brown’s Angels & Demons took the conclave hostage, quite literally. In the tense fever dream of antimatter, clandestine societies, and even a papal kidnapping, the cardinals are picked off one by one as Tom Hanks races through Vatican tunnels to stop Armageddon. It’s all very silly, but also very watchable. That it centered around a conclave gave the film a Hans Zimmer-infused gravitas, even as it drowned it in conspiratorial goo.

A still from ‘Angels & Demons’

Another notable outlier in this canon of cloistered cinema is Peter Richardson’s The Pope Must Die, a 1991 slapstick comedy in which a bumbling, Elvis-loving priest played by Robbie Coltrane is accidentally elected pope due to a clerical error and immediately runs afoul of the Vatican mafia. Unabashedly blasphemous and drenched in the comic sensibilities of British satire, the film treated the papacy as a seat of institutional dysfunction. While it sparked controversy upon release and was even renamed The Pope Must Diet in some markets to soften the blow, the film now reads like a punk riff on Church pageantry.

A still from ‘The Pope Must Die’

More somber, but no less theatrical, is 1968’s The Shoes of the Fisherman, in which Anthony Quinn plays a Ukrainian archbishop improbably elevated to pope amid Cold War tensions. The newly crowned pontiff must navigate geopolitics, nuclear diplomacy, and his own spiritual anxieties. The film plays like Dr. Zhivago in cassock and mitre, but in portraying the papacy as a platform for moral leadership rather than mere symbolism, it too anticipated Francis as the “people’s pope”, who tried, in his own way, to be both shepherd and statesman.

A still from ‘The Shoes of the Fisherman’

Though technically a miniseries, there’s also Paolo Sorrentino’s The Young Pope and its sequel The New Pope — a pair of wildly stylised television sermons that all but demand inclusion in this canon. Jude Law’s Pope Pius XIII strides through the Vatican in spotless papal whites, smoking cigarettes and dispensing cryptic aphorisms like a rockstar-god with a persecution complex. Sorrentino reimagines the papacy as a surreal performance piece with giraffes and softcore nuns, but beneath the baroque excess is a reflection of how the modern papacy has become a media construct as much as a spiritual office.

A still from ‘The Young Pope’

There is also, of course, Wim Wenders’s Pope Francis: A Man of His Word — a spare 2018 documentary on the late pope in which Francis speaks directly to the camera, addressing viewers as if at eye level. It’s portraiture rather than storytelling, but effective nonetheless in painting the late pope as a kind confessor to the world.

Now, with his death, the Church returns to the ritual of succession, as the world waits, again, for a new face to step onto the balcony and wave.

Published – April 22, 2025 05:16 pm IST