While in New Delhi for a literary event, author and media professional Rentala Jayadeva handed a copy of his Telugu book Mana Cinema – First Reel, published by Hyderabad-based EMESCO books, to a writer-friend known for his scepticism towards film literature. This friend believed most books on cinema garnered attention for the wrong reasons. A few days later, after reading the book, he admitted he was pleasantly surprised by its depth and passion.

“I am glad the book made him reassess his view of film literature,” shares Jayadeva, a Nandi Award winner (2011) for film criticism. This year has been eventful for him — the book received rave reviews, and he was conferred the Ugadi Puraskaaram by the Andhra Pradesh government for his contributions to journalism and literature.

Mana Cinema – First Reel, while busting long-standing myths about the Tamil and Telugu talkie eras, also prompted the Telugu Film Chamber of Commerce to declare February 6 as ‘Telugu Cinema Foundation Day’, marking the release of the first full-length Telugu talkie Bhakta Prahlada in 1932.

The book charts the visual medium’s evolution over a century, from silent films to sound, detailing it with trivia. It challenges misinformation and urges readers not to accept ‘facts’ blindly.

It is also a heartfelt call to recognise the pivotal role Telugu-speaking personalities — such as LV Prasad, HM Reddy, Paidi Jayaraj, and YV Rao — played in shaping Indian cinema.

Edited excerpts from a conversation:

How was the seed for the book sown?

The book shaped up from my research. My father, Rentala Gopalakrishna, was a theatre artist, translator, journalist, and author. Despite over 200 literary contributions, he was never awarded an honorary PhD. He was fondly called ‘Rentala’ by peers. I wanted to bring visibility to his name through academic work.

Initially, I planned my doctorate on the evolution of dialogue in Telugu cinema, from silent films to talkies. My guide was not thrilled, but I pursued it for seven years. Eventually, when deadlines loomed and I had to re-register, I was advised to switch topics — to my father’s poetry. I complied, but the original idea never left me. Over the next 14 years, it grew into a book. By December 2024, the manuscript was done, and the book was published.

The idea to trace the evolution of cinema is ambitious. How did you arrive at its structure?

I began by tracing the silent film era globally, then moved to its origins in India, focusing on the transition to talkies, beginning with Alam Ara. I then explored the growth of cinema across Telugu, Tamil, Kannada, and Malayalam. Even though I limited the focus to dialogues, the manuscript was over 500 pages.

The silent film era was eventful — the constraints of sound design, the need to import technical equipment, the rise of Calcutta, Bombay, and Madras as powerhouses. What caught your attention?

Everything about that era fascinated me; the challenge was keeping it concise. Those were fascinating times. How can you fathom the vision of Raghupati Venkaiah Naidu, a photographer at Mount Road in Madras, to build theatres, turn into a distributor, construct a studio and direct films?

An aspect that pains me is the ignorance of South Indians to record our history. Why did anyone not make the effort to verify the release dates of Kalidas or Bhakta Prahlada? How did A Narayanan shoot a talkie film, Srinivasa Kalyanam, in Madras in 1934? One story led to another.

How did you verify the timelines surrounding early Tamil and Telugu films?

In the 90s, I spent the early part of my career in Chennai. I became curious about cinematic history. After work, I attended screenings of world cinema at film clubs and cultural centres. In one instance, a conversation with a film historian gave the book a new direction.

The historian, while revealing proof around the release of Kalidas (which was wrongly proclaimed as the first-ever Tamil talkie) in 1931, challenged me to find evidence to state that Bhakta Prahlada (Telugu film) released a couple of months earlier. His tone irked me. It led me to discover that the latter only released in 1932.

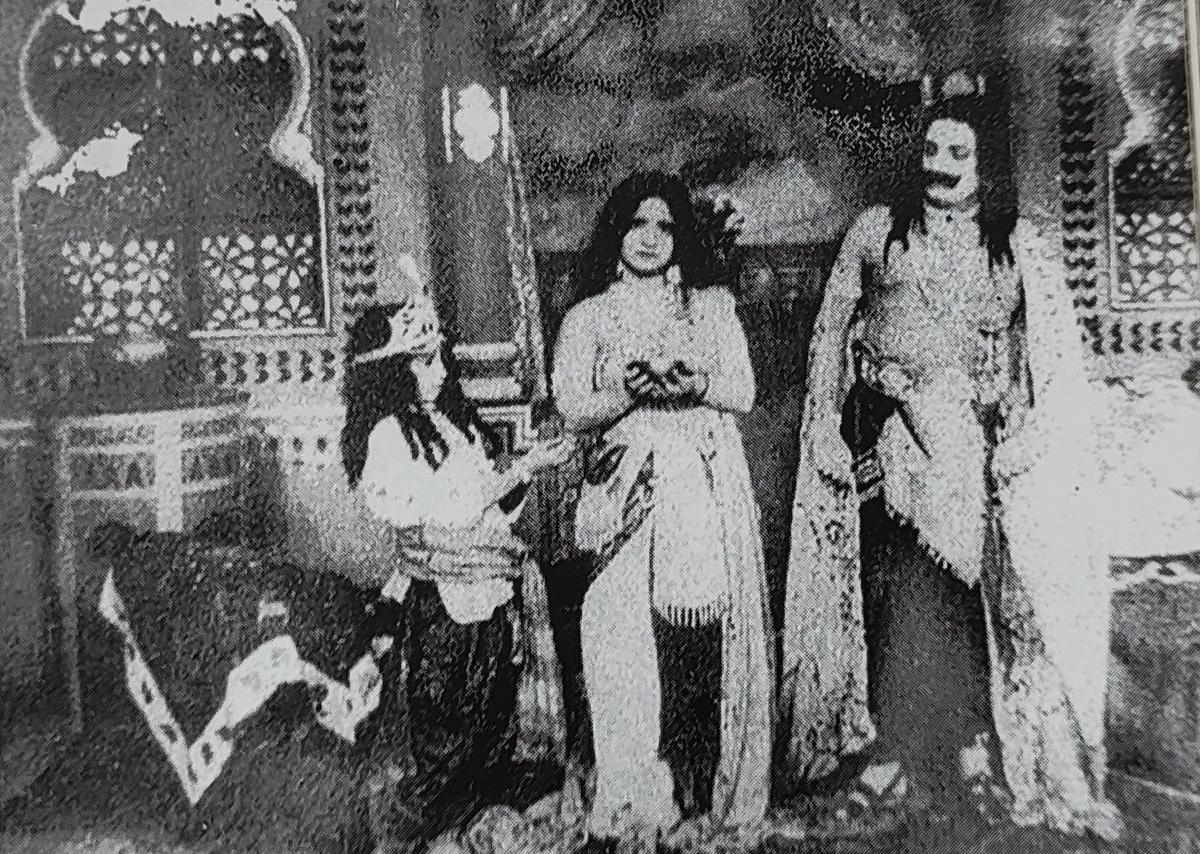

A scene from ‘Bhakta Prahlada’

| Photo Credit:

Special Arrangement

The revelation around Bhakta Prahlada’s release (February 6, 1932) created ripples in the industry. In the process, I found something stranger — that Kalidas was not a Tamil film in the first place. I stumbled upon an interview (from 1931) where the lead actor of Kalidas, TP Rajalakshmi, spoke of rehearsing the Telugu dialogues in Tamil script at shoot. How could our history go wrong? I had to find answers.

The book busts myths around the first Tamil and Telugu talkie…

I drowned myself in research for 13 years. Buoyed by Alam Ara’s success, a Telugu talkie was conceived and HM Reddy was to direct Kalidas, who scouted for new talent in Madras. Popular writer K Subramanyam suggested he consider a silent film actress, TP Rajalakshmi, for the same.

HM Reddy

Modelled around Rajalakshmi’s strengths — in Kuruthi dance and songs (in Tamil) — some segments were shot, after which they filmed Kalidas (in Telugu). It was predominantly a four-reel Telugu film, with Tamil songs, dances, Tyagaraja kritis included as part of the package. A Tamil review by Kalki Krishnamurthy (in the magazine Ananda Vikatan) validates this. I could not wrap my head around the fact that the Telugus didn’t bother to authenticate this for so long.

Why do you think no one questioned the claim?

We may have had journalists writing on Telugu cinema, but most of them were lost in their day-to-day commitments. Moreover, we have very few quality historians. Even my initial intention was not to contest historical claims. When the historian challenged me to find proofs for Bhakta Prahlada’s release, the science student in me was restless.

I ran from pillar to post across cities and libraries poring over documents, newspaper clippings, taking images and photocopies. I was directionless for a long time. It was a painful quest for truth.

The trivia lend raciness to the book. The segments on Alam Ara (1931), Bhakta Dhruva (1934), Balan (1938) are riveting.

I was clear that I did not want it to be a thesis book. If I am to make an average reader aware of the facts, the timelines and varied histories of industries, the book needs to have a strong hook.

My intent is to shed light on the contribution of Telugu people across industries from the 1900s. I want readers to know about YV Rao’s significance in Kannada (actress Lakshmi’s father, the director of Sati Sulochana, the first Kannada talkie), Sarada’s popularity in Malayalam, HM Reddy’s pioneering presence in the early talkie years. For history to come alive, it has to be personalised. I treat myself as a reader first and then, a writer.

If I read about Bhakta Dhruva, I would want to know how they used a dummy tiger to film a scene with a child artiste innovatively. Can you imagine an action sequence in the Kannada film Sati Sulochana was shot using three cameras in 1934? As an avid film buff, if these stories excite me, I’m sure the reader would feel the same. Probably, my journalism experience has a role to play in this.

How did films become a mass medium in India?

Cinema has always wooed the masses, as early as the 1910s, from the time of Raja Harischandra (1913). With Lanka Dahan (1917), there were instances of people coming to theatres in bullock carts. Imagine crowds, for one of the earliest silent films, paid just to watch a train move on the screen.

Whenever there’s a paradigm shift in storytelling, say from stage dramas to cinema, there were hiccups, but crowds embraced the change gracefully.

Film reviews are a touchy topic today. How was the situation back then?

The review of the first Telugu talkie film, Kalidas, by Kalki Krishnamurthy, invited criticism from another publication that claimed his review was harsh. Like this instance from the 1930s proves, reviews could invite a lot of drama from the media and the film fraternity alike. Not much about film criticism has changed in over 100 years.

(Mana Cinema – First Reel is priced at ₹750; available at leading bookstores and online.)

Published – May 15, 2025 03:14 pm IST